‘Shipping companies are killing us’: The explosion in logistics costs won’t end anytime soon for seafood: Intrafish

Aquaculture, fishing and processing companies have been pinched by ‘unprecedented’ freight rate increases. It may get worse before it gets better.

John Evans: IntraFish

A tumultuous period for the global shipping industry since the onset of the global COVID pandemic continues to create headaches not only in terms of higher costs, but also for those trying to work out how to ship products for processing and across the world to customers.

Before the pandemic it was difficult to pass on fuel costs to customers and end consumers, but now shipping companies have much greater bargaining power because of the dislocation of shipping containers around the world, and the spike in demand for everything from microchips to soymeal.

The United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD) released a policy briefing in April that spelled out just how dire the situation has become.

“The increase in demand was stronger than expected and not met with a sufficient supply of shipping capacity,” UNCTAD wrote in the brief, adding that the subsequent shortage of empty containers “is unprecedented.”

“Carriers, ports and shippers were all taken by surprise,” the briefing said. “Empty boxes were left in places where they were not needed, and repositioning had not been planned for.”

The National Fisheries Institute (NFI), which represents North American seafood companies, said the slow-burning issue of shipping costs is taking on more significance among its members.

“The continued effort to find cold storage and cost effective transportation is really something that is of concern certainly,” NFI spokesperson Gavin Gibbons told IntraFish.

“We could see some of the delays at the ports passed on ultimately to consumers in terms of pricing because the situation in the ports is a costly one.”

Some long-term contracts cannot be changed, meaning the higher ocean freight is a cost companies must absorb, said Great American Seafood Imports Company President Sam Galletti.

“Shipping and ocean freight companies are killing us with double and triple-digit price increases,” he said.

On the other side of the Atlantic, the UK Seafood Industry Alliance, a trade group representing the UK’s largest seafood processors, highlighted similar concerns.

“For my members — the bigger guys — it’s actually transport costs which are the most concerning, whether that’s for imported fish, containers, unloading and all that, and stuff coming from further afield,” UK Seafood Industry Alliance Director General Andrew Kuyk told IntraFish.

It’s a similar situation in continental Europe.

Guus Pastoor, president of the European Fish Processors Association (AIPCE), which represents seafood processors, traders and distributors across several countries, said his members have experienced the same strain.

“We have seen container prices up from $2,000 to $12,000 or more,” he said.

Shipping cost rise has gone from ‘temporary’ to ‘long-term’

At the outset of the pandemic, most people were betting on higher costs for a couple of quarters. Now, it’s widely expected the higher costs will run into 2022.

“Prices will be lower than they are now but at a higher level than they were in 2019 in a normal situation,” Rabobank analyst Matteo Iaggati told IntraFish. “That is borderline undisputable.”

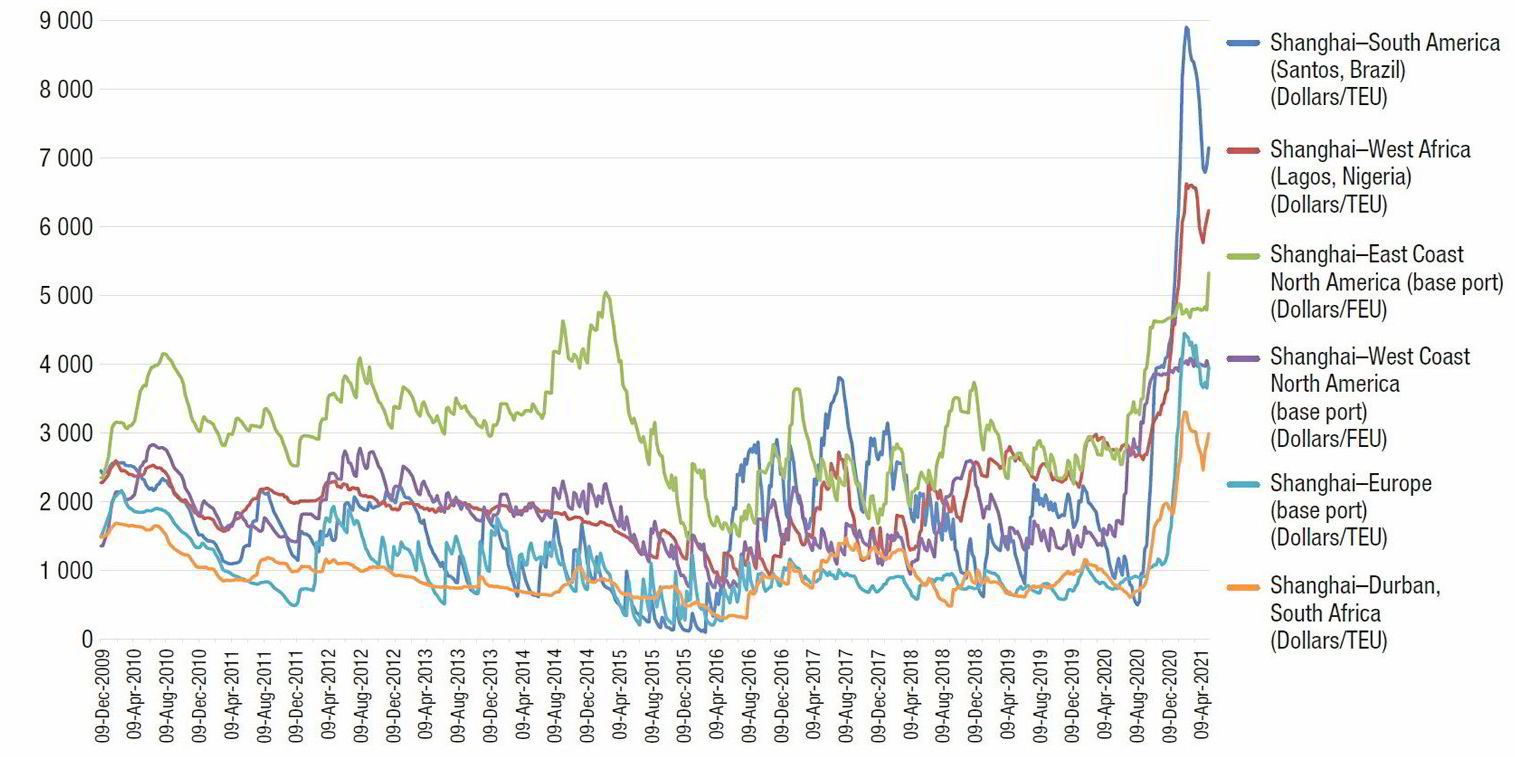

Booming demand for ocean freight, port delays and equipment shortages are continuing to push container spot rates to new heights, with container freight rates having risen to new highs on the three major east-west trade lanes.

Shipping delays may include companies being booked on one vessel but having to put their cargo on the next available vessel.

Meanwhile, charter rates for container ships have hit an all-time high and are expected to remain strong for some time yet.

The record-breaking rates comes as no surprise to analysts.

“With the ongoing and drawn-out demand recovery from the pandemic being met with an ever-dwindling supply-side, rates were only ever going in one direction,” shipbroker Howe Robinson Partners said.

Reefers are a complicated picture

Prices for “reefers” — refrigerated containers used to ship frozen and chilled seafood — have reacted slightly less to the disruptions than dry bulk cargo. Reefer prices were up 26 percent in the first quarter of this year.

Reefer rates, however, are starting to be pressured as dry cargo competes for space on ships, according to Phillip Gray, a reefer analyst with Drewry, a group that analyzes the shipping sector.

Rates to charter specialized reefer vessels, used to get bypass scheduled sailings,have almost doubled since the first quarter of 2019 as exporters look to fill gaps in dry cargo vessel availability and commodities from seafood to bananas seek out extra capacity.

There is little sign of demand slacking, with imports into US container ports in the first half of the year expected to be a third higher than last year.

“This is where we see the ‘engine’ driving the boom in container volumes into North America, as the US consumer continues to favor spending on goods versus spending on services,” Danish analyst Sea-Intelligence wrote in a report.

Misplaced containers

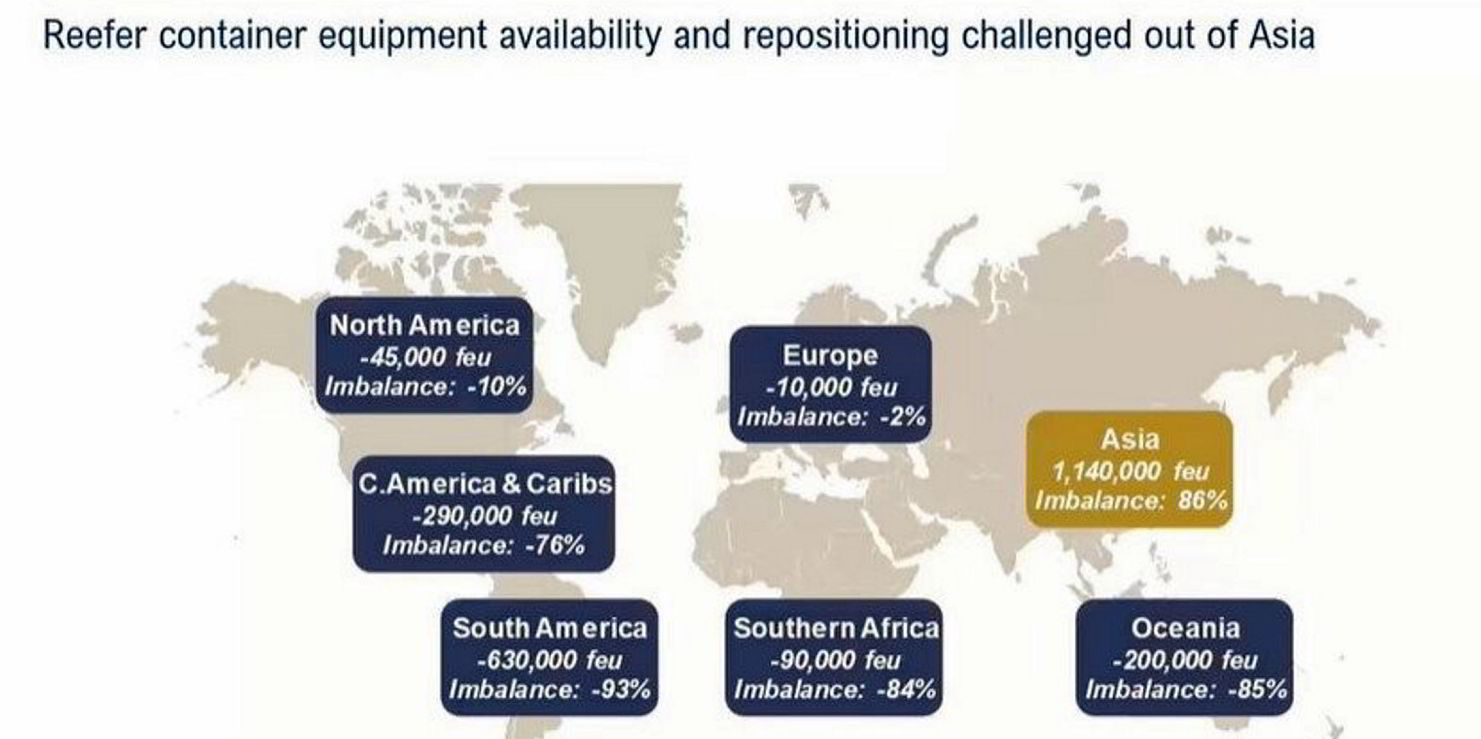

Demand is just one aspect of the rising shipping prices. More complex and more vexing for seafood companies hoping to get product to market on time is that the typical journey of the actual shipping containers has been completely upended.

As COVID-19 in China threatened to spread well beyond Asia, seafood companies in Europe and the United States faced delays in getting containers of frozen processed products back because they were held up by backlogs at Chinese ports working at reduced capacity.

But fast forward and the situation has been turned on its head. Chinese and Asian exporters are facing delays getting containers back from regions on the other side of the world.

“They are missing a lot of containers in Asia following the cancellation of vessel trips in 2020, which continued into the early part of 2021, meaning containers were unable to complete full cycles,” said Rabobank’s Matteo Iagatti.

“The situation now is that containers are still unevenly distributed.”

The container shipping industry is cyclical. Vessel earnings, known as charter rates, fall when there are too many ships in service and not enough cargo, and rise when there are not enough ships, containers or too much cargo to carry.

The amount of containers stranded in the wrong parts of the world has left owners scrambling to keep vessels in service they would have otherwise scrapped, and get their hands on as many containers as possible.

Shipping rates from many origins increased 20-40 percent overnight and some ports of origin such as China, in some cases have literally doubled, Jim Gulkin, managing director at shrimp supplier Siam Canadian said.

Not only is there a problem in being forced to pay exorbitant rates, but even if exporters accept the rate increases, getting container space is very difficult.

“In China, container space is often being auctioned off to the highest bidder. It’s almost blackmail,” Gulkin said.

“Many freight forwarders in different countries offer lower prices but ultimately cannot book containers.”

Backlogs on top of backlogs

The problem of containers being stranded in the “wrong” place was compounded by other events over the past year.

For example, increased customs checks at Chinese ports aimed at spotting COVID residues on food packaging slowed the loading and unloading of containers further.

Disruptions were particularly acute in the port of Dalian — a critical port for the seafood trade shipping product to China for reprocessing. Seafood associations from multiple countries have called on China to relax checks as the country has moved out of lockdowns. Some of the key seafood ports, however, remain closed to exports from certain countries.

Russian pollock harvesters, for example, are still unable to deliver goods to Dalian, a fact that has caused serious disruptions in the typical flow of goods and a scramble to find new markets.

Frank Bodin, vice president of whitefish supplier Nordic Group in the United States, said the additional scrutiny is another huge addition to the already high costs companies face.

“[It’s] causing extraordinary cost increases inside China and also on the freight rates,” he said in a presentation at the North Atlantic Seafood Forum in June.

“Freight has doubled, tripled. Costs of disinfecting, testing and controlling everything is also very, very high.”

A shipping company’s market

For now, shipping companies “have the upper hand” given the recovering economies in the West and their ability to manage their capacity well, Iagatti said.

That’s reflected in the latest rates. At the time of writing, the Drewry global index for all shipping routes combined was 292 percent higher than a year ago and up 2 percent, or $121 (€99), from a week earlier.

A glance at the table shows that with more containers now displaced in Europe and the United States, it has become much more expensive to ship dry bulk cargo from Asia than from European and US destinations, creating a headache for those seafood processing companies processing in the Far East.

When the system gets in a constantly congested state, sensitivity can be higher when containers do not arrive on time, or when inevitable disruptions happen, such as the blockage of the Suez Canal in March by the giant Ever Given containership.

Hundreds of ships were stuck around the Suez for several days, generating delays and congestion, lifting prices even further and compounding the uneven distribution of containers.

“If we have other disruptive events, maybe not as big as Suez, we are now in a situation where every little mishap reverberates in a situation that is already fragile,” Iagatti said.

“So every addition to the precarious situation that global supply chains are in now will make container prices go up.”

Regardless of how any of the supply or demand issues play out in the coming months, Iagatti has a bleak message for any companies shipping goods: “You are looking at a period of sustained [high] transport prices.”

Eventually the situation will improve but that won’t be soon. Siam Canadian’s Gulkin expects to see high freight costs and a shortage of containers and available vessels at least until the New Year.

The higher freight costs will ultimately have to be passed on as the increases are simply too big for processors and exporters to absorb, in his view.

“Other than passing the costs on, there is nothing that can be done to mitigate costs,” Gulkin said.

“The shipping lines could, in fact, do a tremendous amount to mitigate the current situation but perhaps it’s not in their best short-term interest to do so.” fragile,” Iagatti said.